Last Supper

A breeze blows down through Casa Aurel. I straighten my back, easing the stiff vertebrae, and feel the sinking sun on my neck. Laughter bubbles over from the third floor balcony, while at street level Alice emerges from the front door. She smiles and plucks a sprig of rosemary – ‘for the bread,’ she tells me, before disappearing.

Bike wheels, allen keys, jiffy bags and masking tape are strewn on the narrow street in front of the yawning bike bag I am attempting to load. Just a week ago, in a kitchen north of Nottingham, dismantling this bike was a drama. Seven suns and many miles later, it is a task I know I can tend to.

Laughter erupts again. It is a familiar sound now – the song of nine women that has filled the house each day since we arrived – but in the beginning it intimidated me; joyful, free, utterly unselfconscious, things that I am not. It rattles the two flights of stairs from the kitchen, dives from the balcony and splashes against the whitewashed stone walls of the cave-like bedrooms. There’s nowhere it doesn’t penetrate and there’s no ignoring that it is an important part of our journey.

And what a journey. While the advert for The Adventure Syndicate’s Spring Gathering had promised eight women ‘the support they need to experience their own bikepacking adventure’ I am leaving with a glimpse of a new perspective, an experience that goes far beyond bikepacking.

And our time is nearly up. Upstairs they are preparing paella, laying out bowls of thick hummus and loaves of freshly baked bread on the long table, all the while singing to Meatloaf and other dubious (but delightful) soundtracks.

Hopes and fears

That first night, we are eight strangers around the same table, full with Alice’s risotto. Lee makes nine. When I think of her I can’t help but see caramel – strong, sweet, hard to break. It’s in her voice that eases and stretches, the orange-brown streaks in her tangled blond hair and the constellation of thick brown on her sun-scorched cheeks.

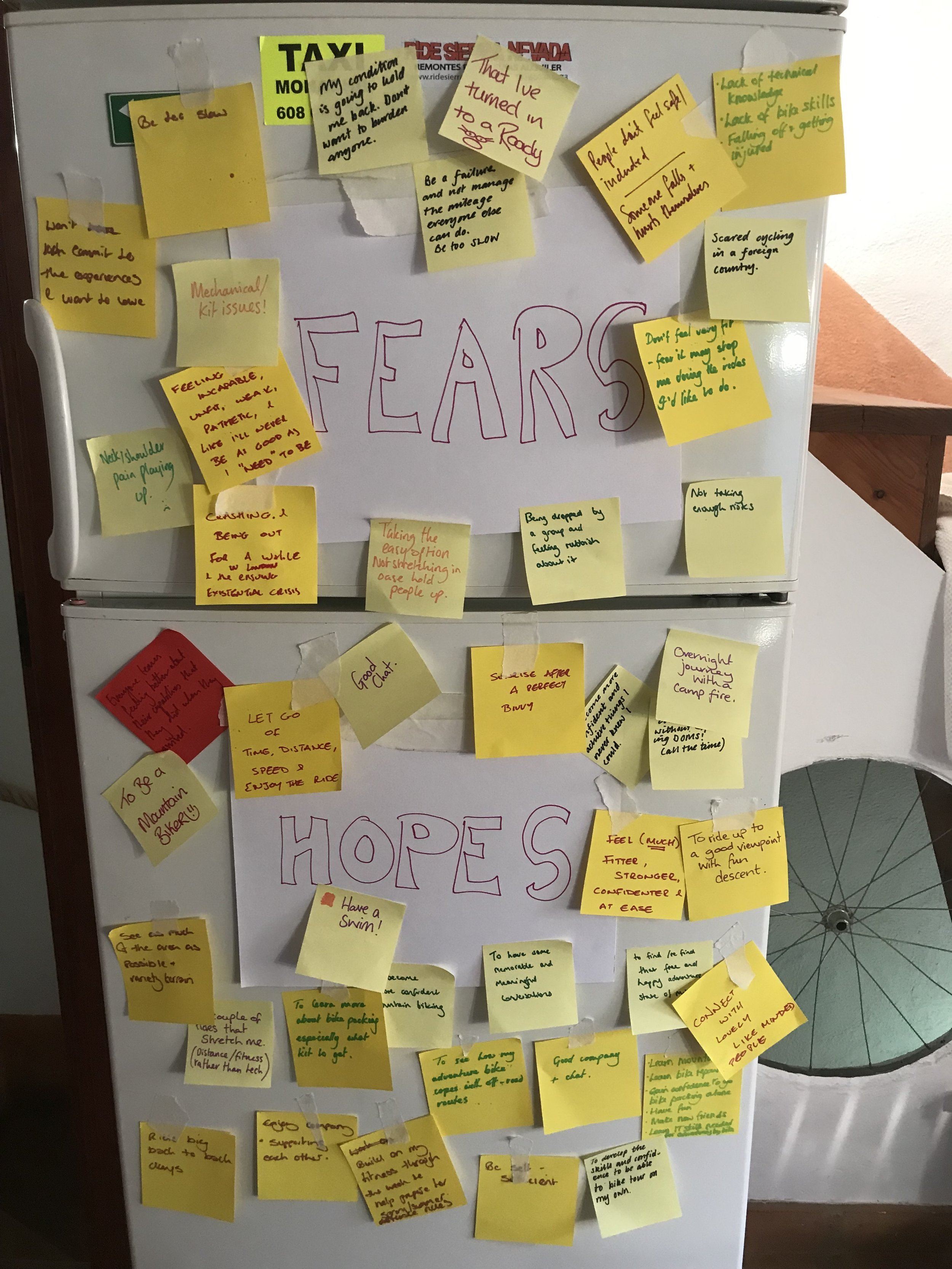

After dinner, Lee hands out coloured note squares and pens and asks if we might like to write down our hopes and fears for the week.

There is quiet for the first time. Chairs scrape as, one by one, we get up to post up our little squares full of words onto the refrigerator, where they will remain as long as we do.

These notes will become our personal contracts, Lee explains, adding, ‘if you don’t leave here, if you don’t quit, they stand.’

The conversation falters. Perhaps we are all contemplating those things that we want most and the barriers that stand before them. ‘Would anyone like to share theirs?’ Lee asks. Janet speaks first; she falters just a little as she tells us all that she has Parkinson's Disease.

‘I’m right handed but I have to do everything with my left,’ she says with a little laugh, ‘and, if I have to do a right hand corner I might scream.’ As she looks wide-eyed around the table I think of my barriers. I’m sure every woman here has their own; I wonder how many of us would be here in Janet’s position. She is life-affirming. As I watch her and listen as encouragement and support are passed across the table, and steadily, the laughter resumes, I feel for the first time how different this experience is likely to be compared to simply counting pedal strokes, cadence, miles and feet.

The start of things

The day vibrates inside me long after it is over.

We climb to the village of Guejar Sierra as a group, stretching out down the 8km climb as we take it at our own pace. After coffee we split, just Kate, Lee and I heading further up the hill to find a rocky single track descent, while the others head into the hills for more road miles.

While I try to find breath and admire the pom-poms of almond and cherry blossom scattered along the otherwise brown valley, I tell Lee I’m from Nottingham. She reminisces about how shit the Sherwood Pines National XC Races were. I agree and confirm they are still are. And at the same time I try and fail to imagine her tearing around our safe single-track.

Later, kneeling on the ground to release air from my tyres in the hope of cushioning the blows from the rock gardens, a scent - sharp, musky - rises around me. Rosemary. Looking at the stubby plant beside my front tyre, thinking of delicious stew and golden roast potatoes, I feel a moment of relief from the fear and intense desire to perform that have been driving me down that trail.

‘My eyelashes hurt, my skin hurts, my eyeballs hurt!’ These are the first words from Janet’s lips and as she staggers into the kitchen. She and Helen have had a big day. But this does not stop her taking over dinner prep, showering and heading out with a few of the others for jazz and Drambuie, while I crawl into my cave and welcome sleep.

New Light

‘It’s a mind shift. That’s why you’re here.’ This is what I tell myself as I follow Jenny Graham up the steep tarmac climb into the Sierra Nevada National Park.

How much effort is she actually putting in? Is she keeping it steady for us? Or is this her flat out? How long can I keep this up? The competitive voice in my head never quits and here it is asking me to try and keep up with the woman who holds the world record for riding around the world unsupported. At home, this voice drives me to unhappy places but in that moment I have to laugh. I know it for the sham it is and somehow I know there is a better source of motivation; plain old ‘just keeping going’.

As we hit gravel, climbing some more, she tells me she’s raced the Arizona Trail and that’s aside from the Highland 550, The Cairngorm Loop and God knows what else. She goes on to explain that she’s like a Diesel engine. She just keeps going. When she arrives on any start line she feels intimidated. She tells me she doesn’t feel like a racer. I think about my frantic desire to prove myself. Does she ever feel this way? I don’t dare ask.

Instead, I can only think of the doors Jenny must have opened, in her body and mind, to achieve what she has. As we go higher into the mountains, snow-capped peaks in the distance, I’m overwhelmed by possibilities. The sky feels wide and the light sharp and bright.

My fear

‘What are you afraid of?’ Sarah asked, taking a break from fettling her bike when I admitted to her I was afraid to embark on the solo ride I have planned. ‘Well,’ I began, ‘having a mechanical that I can’t fix, getting lost, being unable to read the map, becoming too tired to carry on.’

‘Can you deal with those things?’ Sarah watched me, smiling, blinking, leaving space for my answer. ‘Well, mostly. I have two maps, I think the route is pretty simple. I know it's all downhill on the Sierra road and I’ll know where I am when I get there. I have my phone and a charger in case there’s a problem. Yes, mostly I can deal with those things.’

But as I climbed the tarmac above Monachil I knew I could not deal with it. Because the fear had little to do with mechanical trouble, map reading or fatigue. I was alone, and that was what terrified me.

I could have returned to the National Park with Kate, Fiona and Sarah but this solo ride, climbing into the mountains to locate the gravel track that would take me back to where we were on day 1, was what I chose. I had approached this gathering as a place to push boundaries, to find new things. Going out there on my own was pushing me right to the edge and I felt I needed to go there. I’d arranged to meet Jenny at the start of the single-track and this gave me something to hold onto.

If there are good climbs, the 20km drag to Tocon is one of them. A gentle meander past juicy cacti and delicate blossoming trees. I was on the right track – Wahoo said so and Kamoot agreed. My bike was working. Everything was good. But my breathing came rapidly and my chest felt drum-skin taut; I looked at the jagged rock walls that were drawing up around me the higher I climbed and I imagined clinging to them, fingers slowly losing grip before I began falling.

In Tocon, a cat rattled a bin lid and the only thing missing was tumbleweed. The bar was shuttered and the streets deserted. No paved roads beyond, just gravel that wound into the hills, climbing with the same gentle ease, taking me higher and deeper into nothing. It was just me and the land scored with tracks and patch-worked with terraces.

‘This is beautiful,’ I said to no-one. I believed it; I just could not feel it. There was no space for anything in the pressurised cavity of my chest.

‘So, how was your ride?’ Jenny smiled widely between mouthfuls of the melted cheese she was scooping out of a plastic tub.

‘I’m in bits,’ I told her, unable to manufacture the enthusiasm I know she would have had in my situation. ‘The ride was great, it’s just there are other things going on for me. I felt so afraid and alone. It’s not the ride. It’s more about a terror of abandonment I had as a child.’

We were pedalling again. ‘Are you getting help with that?’ She called over her shoulder as she takes the lead where the track narrows.

It’s hard to bare a soul while negotiating rock gardens or a herd of goats that are casually grazing steep, loose switchbacks. And once we were safe again, cruising the streets of Granada for fizzy drinks, something was lingering in the place that the fear had filled. I could barely speak. When Jenny plopped down in front of a convenience store, given over to Coke and more gooey cheese, in a way I think must have been the norm when she was racing around the world, I couldn’t even laugh.

That evening the house was vibrant. Fiona was high on stoke having taken Lee’s Juliana into the National Park. Janet had enjoyed a day off, Helen had made it back from the hot springs to report on the population of naked hippies and Alice and Lee had been to the coast. I couldn’t touch their joy. Something stopped me from reaching out to them, something I didn’t understand in the moment, but later recognised as the ugly cloak of shame. I watched Jenny’s demonstration of kit for our bivvy night and made careful lists of food and equipment. All the time I had a sense that the world was shaking, trying to fling me off, but if I just held on...

The centre of things

Burdened with sleeping bags, mats, warm clothes, food and stoves, we climbed the road to Purche, striking a poor contrast to the road race that had flown through there days earlier. Kate, Fiona, Sarah and I were in no hurry. We stopped from time to time to examine the olives hanging in the trees that line the road or devour one of Janet’s scones. We were climbing into the National Park to find a bed for the night; we simply had to be there by dark.

Beyond Purche there was the feeling of being swallowed on the tongue of gravel that delved deeper and deeper into the rock canyons. And while I normally hate climbing my legs found a steady rhythm where I settled to thinking - if I could pedal into the Spanish countryside alone, as I had the day before, I could do that at home, say into the Peak District, where I and others have told me I cannot go alone. And, if I could do that, what else could I do?

Those 12 hours in the Sierra Nevada National Park became a centre of sorts. The core of an experience that had been stripping, harrowing and tenderising my insides, not to cause harm, but to make them ready for something else.

We watched the sunset over the city below, heated couscous, cheese, vegetables and hot chocolate and huddled against the creeping cold. This was Janet’s first time camping. Ever. And she was doing it without canvas, beneath vivid shooting stars. Long after I had slunk to bed, itchy, tired, with cold setting into my feet, I could hear her voice and others’ laughter. In turn, I felt a creeping loneliness as I pressed my hands between my legs and wriggled deep down into my bag to keep off the breath of the night.

After breakfast and once the squeezing, stuffing and ratcheting that is bikepacking was complete we all came to sit. The herd of bullocks, whose dry, dung scattered territory we were squatting stepped closer to listen in.

‘First of all we are storytellers,’ Lee began, ‘we have adventures so that we can tell the stories. But they are not just our stories. This is about your voices too –’

In that moment I was utterly awake, listening, aware of nothing else. For once there was space enough inside me to equal this hillside and the mountain range beyond. I didn’t know I needed to hear words like these or that they would fit in the way they did right now, in a way that made me want to stand and shout, ‘yes! Yes! YES!!’ But is seems I did.

Here we were truly gathered, still despite the discomfort of sitting on tinder-dry logs. In this place everything stopped – the fear, the judgement, the need to protect myself – and I was ready to begin again.

My hope

I listened as my companions shared their experiences, softly, slowly. Janet confirming she’d had no idea what she had signed up for, that it was a challenge she could not comprehend but that she had met it. Kate explaining the enjoyment she found in the freedom to choose the rides she did. Fiona enjoying the experience of spending this time out on the bike and knowing the limits of her gravel bike for the type of rides she wanted to do back home.

I couldn’t explain what I had found. I didn’t know. So I held it inside of me as I followed Kate along the exposed single track known as The Scratch and then alone through the woods to the village and to a table on a sun-baked balcony where I could empty it all into a notebook with a moist black Bic.

That week I revisited the fear that has haunted much of my life – one that paralyses, that feels like being held underwater time and again, one that belongs to a five-year-old girl, not a 39-year-old woman. I observed the anger, the intense desire to prove myself that flows from of it, and the blanket of shame I’m often wrapped in and which keeps me separate from the people around me. But for one of the first times in my life, I truly saw beyond all that. I saw another path, all the way to the mountains, if that’s where I choose to go. My challenge is to remember the view and the road I must take to get there.