Sport is full of extreme contrast: one moment you feel indestructible, the next you are almost weeping; one day you feel amazing, the next you feel wrecked. A few weeks ago I became a Paralympic champion. I felt physically fit and mentally strong. Now I feel exhausted; my body the most broken and tired I can remember, and mentally everything feels discombobulated. My head has been spinning – actually a positive sign, as it means my brain hasn’t settled into the cabbage-like state it was so often in whilst training for the Paralympics. It also seems a good indication that I haven’t sunk into the POD (Post-Olympic Depression) state apparently so common amongst athletes after a major event that has absorbed them for a chunk of time. (Apparently Michael Phelps struggled for two years after London 2012, with depression and rehabilitation from recreational drug addiction). However, it seems unbelievable that last month I won a gold medal, given that a few mornings ago my arms and shoulders felt so heavy and sore that I struggled to get myself out of bed

Sport and high performance are usually billed as good things, held in high esteem, presented as something to aspire to. And sport at elite level may well begin rooted in passion and enjoyment, but at what point does it becomes a form of addiction or obsession? Training hard is a habit that is difficult to break. In these post-Paralympic weeks the only way I feel able to give myself the rest I need so much is to go away somewhere, without my bike and with no easy access to a gym. If they are anywhere near me, I will surely be tempted.

As I rest up, I reflect on the pros and the cons of my chosen path as an athlete, on the amazing journey it has been so far but also the more challenging aspects.

On the good side, my job is to ride a bike every day. I am an active person and happiest when outside, and it is a privilege to be able to do what I love, and love what I do. Gone are the days when I was chained to a desk for forty hours a week. I get to ‘live my dream’ in so many ways. For the most part, sport keeps me fit and healthy, I get to see the world, and I meet people from so many different countries, cultures and backgrounds. I mean, how good can it get? How can there be any down sides?

Well, I live out of a bag for most of the year. I am nomadic. Last year I spent approximately five months in rented apartments or hotel rooms. Athletes are relentlessly structured in their training, but have little structure in the rest of their lives. Socially and in other ways, things have felt somewhat out of balance for a while. I’ve missed weddings and funerals, family occasions and special times with friends. What kind of person does this make me?

I suppose that if we’re going to strive for anything good or surprising in life, then focus is bound to be required and some things will have to be sacrificed. It’s always going to demand hard work, perseverance, pushing through when we’d sometimes rather not. It’s always going to draw blood, sweat and tears alongside moments of passion, excitement and euphoria. How sustainable is it though, if our life is out of balance for too long?

The same two questions are fired at me almost every day right now.

“How does it feel to have won gold?”

“What next?”

These questions trigger an avalanche in me every time, though in truth they are already constantly tumbling through the gullies of my mind. I just don’t have answers to them yet.

How does it feel to have won gold?

That’s the easier one to answer. For a few hours it felt fantastic. I experienced a cocktail of surprise, relief and happiness; a mission accomplished, a dream achieved. With that successful race, I became the guardian of a gold medal, and that is a special and privileged thing. It carries magical powers. People’s faces light up when they hold it. They want selfies with it. They tell me things they might not otherwise. It’s an honour to experience the magic of the medal at work.

Whenever anyone first holds the shining golden disc, they always comment on its weight. This disc of gold with its pebble-shaped imprints and seeds that shake inside represent something special. It is physically significant and heavy. However, being its bearer at times also feels significant and heavy. I am grateful to be this person, but it feels somehow that with the medal comes a responsibility, to share the experience, to ‘inspire’ people, to join parades, to speak to school groups, to spread the magic. That is very much an honour, but recently the intensity of it has felt overwhelming.

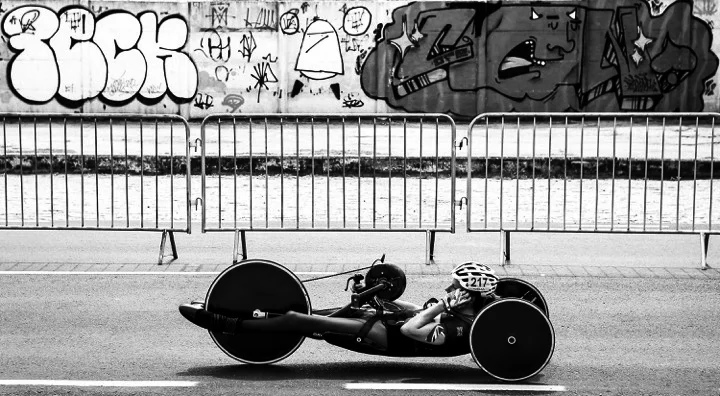

As a Paralympian, I sometimes feel like an actress stepping onto a stage; part of a collective drama about the good that can come from the challenges of life. I am part of the ‘Superhuman’ performance; we embody strength and courage, have fighting spirits and transform challenge into success. I, and other Paralympians, are billed as ‘Superhuman’, but we are no more or less human than anyone else. Life has thrown us the hand it has, and we do our best to engage with it positively. That doesn’t mean there aren’t days when the daily irritations don’t become too much. There are occasions when I feel frustrated and upset; when the disabled toilet is locked again and my long-lost special ‘Radar’ key is still lost, when the train staff haven’t had the training in how to use the new lightweight ramp so I have to stay on the train thirty minutes more to the next stop then get a taxi back, when the disabled parking bays are full of people that apparently don’t need them …or whatever the trigger may be that makes me want to curl up or give up. We are inspirational only because by the nature of our situations and our choice to engage with those positively, rather than the alternative of being miserable. Perhaps we confront people’s self-perceptions. It’s probably human to endemically doubt our inner strength. Ironically, the night before I was paralysed, I commented to a friend “I would rather be dead than paralysed. I can’t imagine anything worse.” How wrong I was! We are all stronger than we might think, braver than we might believe, more able than we might feel. It is only when life forces us to call on those inner resources that they have the chance to appear.

And how else does it feel? Well, for a year or two I have been driving a very fast car; I’ve been on a rapid, busy highway, dodging traffic, accelerating ever faster towards my destination – Rio. And the car just lost control and crashed. I have emotional whiplash, thrown by the recoil of a sudden stop after striving so hard for so long. From a rigidly structured routine has emerged a sense of chaos. The physical focus and constant pushing has exhausted me.

I drove my real-life car along a regular tough training route last week, and felt nauseous recalling the memory of riding my bike so hard there, again and again. People message me – ‘You must be on cloud 9!’ – but instead I am on a very rare cloud, one I’ve never visited before. The medal represents something interesting to me. It is not about being the best at my sport – that is something very temporary and, in truth, any one of four women in my race could quite probably have won that day. It represents a journey of belief. I had a belief that if I wanted to win gold enough, if I focused enough, if I trained enough, gave enough and sacrificed enough …that I could do it.

I called it ‘Project Gold’. Almost every thought and action I have had for the last four years has been focused on gold in Rio. Even though I don’t normally like the shine of gold (gold is bling, silver is classy…), I bought gold pumps, a gold phone, gold laptop cover (though a 6-year-old informed it was ‘rose gold’!), had gold mottos; people gave me gold good luck cards, gold cakes, fake gold medals… It was gold, gold, gold all the way. Going for gold was an experiment. It was a test of the power of thought and belief. I wanted to see how it would go.

And it seems that setting such a strong intention worked its magic. Going for gold absorbed me physically, mentally and emotionally. It drew other people in too. It became moving and powerful to feel the energy and enthusiasm of others. Both friends and strangers were talking the language, encouraging me to ‘go for gold’. I felt the support of people in the organisations that I collaborate with: B. Braun, Berghaus, the team of engineers at Williams F1 who committed so much time and energy to designing a new bike; the staff at Adidas across Western Europe who helped fund the bike. I felt the positive energy from coaches and sports organisations; from people in the UK rooting for the country’s athletes.

So was the gold medal a product of my decision to believe and focus? Whether something in life is the result of destiny or a decision is always an interesting question to me, and Rio has given me a lot to think about. My regular training treat is a chai tea and I always ask for it extra extra hot. Just before I left for Rio, the Starbucks baristas informed me I should be more specific and ask for my chai at 79 degrees. I’ve since had people ripping me for being so picky and westernized asking for my drink at a particular temperature. But the number 79 seems to have cropped up a lot since. On race day the forecast said it was 79 degrees Fahrenheit. The time trial gold I won was the 79th medal for Great Britain. 79 seems to be my number.

The 79th degree east meridian runs through Tibet – a place I went on my most recent adventure in 2014, to recover from some tough stuff in life and to ride the ‘Friendship Highway’ via the mother of all mountains and down into Nepal – so that I could get my head back on track for Rio training. The 79th degree west meridian runs just off the coast of Chile – a place I will soon be going to ride the ‘Wild Highway’ along the coast of Patagonia – to help me recover from the intensity of the Road to Rio. 79 degrees north goes across Greenland, a place I skied across ten years ago, a journey that changed the course of my life. 79 degrees south runs through Antarctica, a place I’ve always wanted to visit. Interesting. I don’t know anything about numerology, but number 79 has got my attention.

And the question of ‘what next?’

It feels too soon to say. I’m in need of more Rio decompression.

“Tokyo 2020?” people inquire.

Some enthuse “You have to go for that!”

Others offer their opinion “You’re getting a bit old for this aren’t you?”

Am I too old? Now that’s an interesting thing to muse on…

Twelve days before my races in Rio, my left shoulder started complaining, feeling raw and painful. Regular ice and physio helped, but it felt that I was just patching it up to keep going. Finally I succumbed to an MRI shoulder scan, and began to wish I hadn’t when the consultant informed me “You have the shoulders of someone at least twenty years older. You have arthritis and a piece of cartilage floating around in there.”

His words immediately imprinted a highly unhelpful thought in my mind. I have the shoulders of a 70-year-old. Since then I have been moving myself around timidly, feeling scared to train or ride my bike, almost fearful of everyday simple movements. I am suddenly behaving as if I am old. The consultant’s verdict temporarily spiraled me into negative thinking. I sat in post-Rio convalescence, gazing through the window at my young nephews playing in the garden. I thought how nice it must be to be so young and energetic, to have bodies so nimble. I imagined myself becoming more and more decrepit, less able to be active and independent. Then I caught myself.

“WHAT ARE YOU DOING TO YOURSELF WITH THESE THOUGHTS?!”

Of course the strain on my shoulders is immense, not only from training, but from the everyday work they do: climbing in and out of cars, chairs and beds, hauling bags and pushing me and my wheelchair around. I love my shoulders and what they do for me. I’m grateful and amazed they don’t complain more. They have been carrying my body and spirit through adventures for almost 25 years! As I contemplate the proposed medical options for treatment, I also reflect on the other possibility – that the past year, with my busy head and busy life, has got them into this state. I strongly believe that our body responds to our state of mind and soul. If we’re happy and have essential parts of our life in balance, then our body will usually be happy too. The ‘Road to Rio’ took a lot, not just physically but mentally too: the juggling, planning and general ‘head noise’. It is likely that my body is responding to the stress and pressure it has been under. I reason that arthritis can’t have got drastically worse in the last few weeks or months. The possibility exists that if I settle, my shoulders will settle.

So, instead of panicking about what medical treatment may lie ahead, or agreeing to anything radical too quickly, I am in search of peace and harmony for now. I have been longing for wilderness and the healing power of nature. ‘Stay well in mind and the body will follow,’ I tell myself. I managed a mini-break to the Outer Hebrides; a boat rocking its way across a rolling swell is a great way to force a rest. A seascape and a whisking from a wild wind up on deck never fail to blow some of the junk away. Gradually I felt my metronome slow down; a few special friends, some good chat, a dose of nature, escape and the simple life, free of 3G (or whatever G we are on now, and whatever that means). Strangely, a ferry ran aground in the Hebrides just before our visit, making headlines for the 79 passengers stranded. Well well well…

And more wilderness is to come. Next month I will go 79 degrees west, to the mountains, forest and lakes of Patagonia. There will be just some wheels, a tent, a few essential belongings, some trusty companions and miles of emptiness. On the one hand I can hardly wait, on the other I am nervous, grown accustomed to hotel beds, less at home than I once was at surviving out in the wild. My hope for the Patagonian journey? A transition from a life focused on racing fast, a reminder that after all, life is a journey not a race.